Treasure or Trouble? The Deep Seabed Mining Dilemma

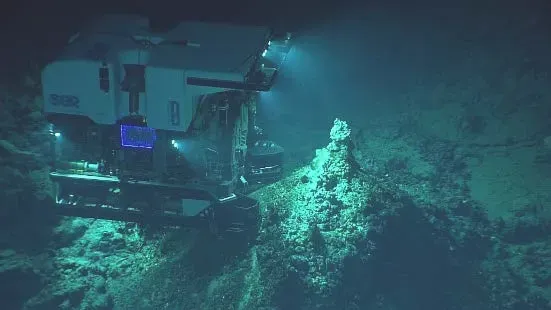

Source: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas

Commentary by Danel van Mensel, Intern, ICES

August 26, 2025

As the International Seabed Authority (ISA) concluded its 30th Assembly in Kingston from July

21-25, 2025, the outcome was clear: no exploitation licenses have been approved, and the

much-anticipated Mining Code remains incomplete.

Member states reaffirmed that commercial deep seabed mining cannot proceed without robust regulations

and sufficient scientific knowledge.

Deep seabed mining (DSM) refers to the

extraction of mineral resources - such as cobalt, nickel, manganese, and rare earth elements -

from the ocean floor, typically at depths of 4,000 to 6,000 meters. These minerals are

essential for clean energy and defence technologies, as well as for AI development. Most DSM

activity targets polymetallic nodules found in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific

Ocean, located beyond any country’s national jurisdiction. As such, DSM falls under the legal

authority of the ISA, which is mandated by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to

regulate exploration and exploitation in the international seabed area (“the Area”) for the benefit of all humanity.

Once a hypothetical opportunity and challenge

for future generations, DSM is now very much a live issue. Triggered by Nauru’s

invocation of the “two-year rule”

in 2021, the ISA has been under mounting pressure to finalize its Mining Code and respond to the

first potential commercial applications for exploitation. That deadline technically expired two

years ago - yet no exploitation license has been granted. With the absence of an agreed-upon Mining

Code, the recent session reiterated that mining cannot commence

without a complete regulatory framework.

At stake is not just a technical rulebook, but the very principle that the seabed

beyond national jurisdiction constitutes the “common heritage of mankind” - a cornerstone of the UNCLOS. In an era of growing demand for critical minerals essential

to the green transition, that principle is being tested like never before.

On one

end of the spectrum, China has embedded itself firmly within the ISA framework. As the largest

holder of exploration contracts and an active participant in rule-drafting, it champions a

rules-based yet strategically pragmatic approach. On the other, the United States - still

outside UNCLOS - has opted for an openly unilateral path. A

2025 Executive Order

by President Trump encourages U.S. companies to begin mining under alternative sponsorship arrangements,

primarily through small island states like Nauru and Tonga. This risks fragmenting the legal framework

underpinning deep seabed governance.

In between lies the European Union, which has

increasingly aligned itself with the global environmental community calling for a moratorium

or at least a precautionary pause. Eleven EU Member States, alongside the European Parliament,

now oppose DSM in the absence of robust scientific and legal safeguards. While Europe also

needs critical minerals, its strategy emphasizes circularity, recycling, and terrestrial

alternatives - an approach that positions the EU as a cautious guardian rather than an eager

extractor.

Norway, by contrast, continues to maintain a more

pragmatic position

on deep seabed mining. Unlike much of the EU, it has not called for a full moratorium and has argued

that Europe's reluctance could result in falling behind countries like China that are accelerating

their seabed resource programs. Norway supports accelerated negotiations under the ISA, but with

careful environmental safeguards rather than blanket delays.

The 30th Assembly

represents progress in strengthening the ISA’s institutional framework, but the Authority

remains at a decisive juncture. The path forward is clear: finalize a Mining Code grounded in

rigorous environmental safeguards, equitable benefit-sharing, and transparent governance, or

risk ceding authority to unilateral actors whose actions could erode multilateral ocean

governance.

For Europe and China, this moment presents both a challenge and an

opportunity. As major economic actors with significant stakes in critical minerals, they could

choose to jointly champion a science-first, rules-based framework that ensures DSM proceeds,

if at all, as a carefully regulated global endeavour. While such collaboration may appear

ambitious given their differing strategic priorities, even limited alignment could enhance the

ISA’s credibility and help safeguard the Area from becoming a new domain of unregulated

resource exploitation.

Please note that views expressed by the author do not reflect the policies or positions of ICES.